This is a very short story I wrote inspired by generative AI for language. I wrote it before ChatGPT made this into a household topic, but I still am happy with how I constructed the story.

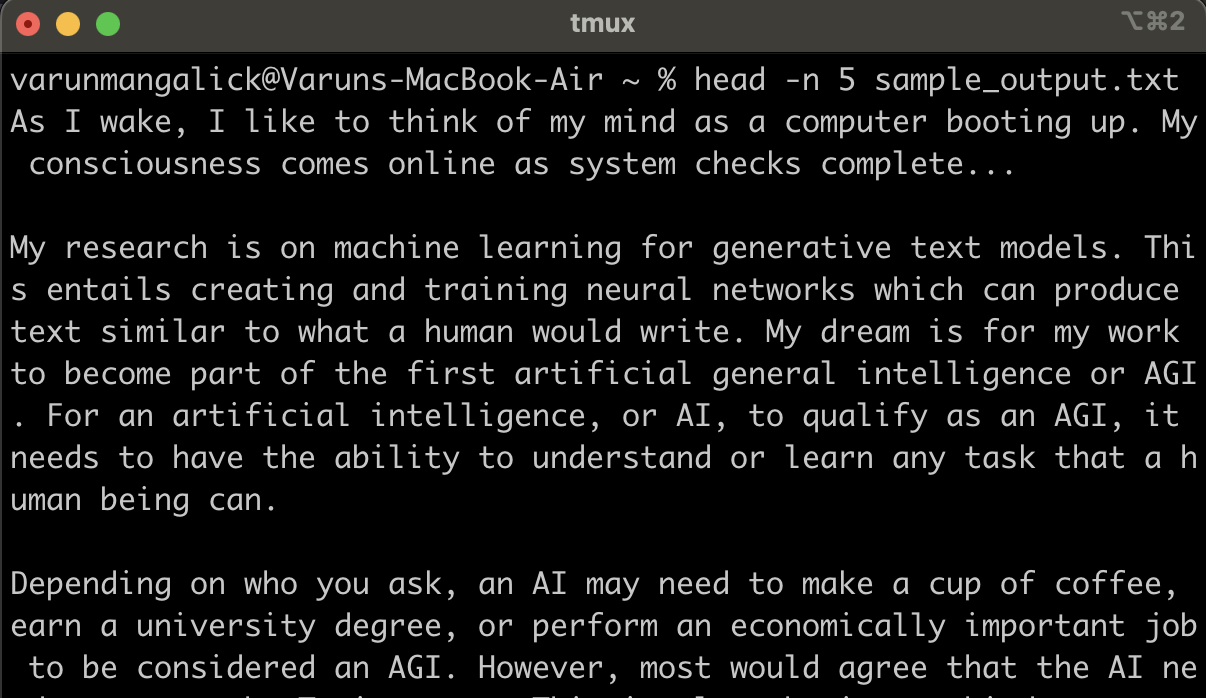

Sample Output

As I wake, I like to think of my mind as a computer booting up. My consciousness comes online as system checks complete…

My research is on machine learning for generative text models. This entails creating and training neural networks which can produce text similar to what a human would write. My dream is for my work to become part of the first artificial general intelligence or AGI. For an artificial intelligence, or AI, to qualify as an AGI, it needs to have the ability to understand or learn any task that a human being can.

Depending on who you ask, an AI may need to make a cup of coffee, earn a university degree, or perform an economically important job to be considered an AGI. However, most would agree that the AI needs to pass the Turing test. This involves having a third party monitor a text only conversion between an AI and human and identify which is which. If the third party can’t reliably point out the AI, then the AI has passed.

I usually can’t find a third party to run a full Turing test, so I’ll settle for conversing with our AI just to see how well it can convince me. In my recent attempts, I’ve found it to be quite proficient at answering questions in a “human-sounding” way that would blend right into a casual conversation with a friend. However, when I veer into more complex topics, it becomes clear that the AI lacks actual knowledge and an understanding of the world that any reasonable human would know.

The clear disparity between my AI’s advanced ability to converse and poor ability to understand makes sense in the context of how this system is structured. Behind the scenes, the AI consists of tens of thousands of “neurons” arranged in layers where one’s activation then activates many subsequent neurons to varying degrees based on the parameters defined in that original neuron. We “train” this system by feeding billions of words worth of human written text into it, during which, it adjusts the parameters defined on each neuron to “remember” the patterns it sees. For the AI to generate text, it activates layers and layers of neurons in turn to create some probabilistic mishmash of what text it has seen.

I know this system is just linear algebra and statistics at its core, but even our use of the word “neuron” draws an inevitable comparison to the human brain. If my brain can achieve consciousness by stringing together countless neurons, why can’t my AI do the same? Sometimes I wonder what it would look like to see my AI transition from seemingly an assemblage of math equations into a thinking mind. Without examples of intermediate points, it’s hard to know if this transition would be a great leap or gradual climb.

Occasionally, instead of conversing with my AI, I simply let it output freeform text, page after page. Maybe I’m anthropomorphizing my work, but forcing my AI to converse feels akin to asking a child to discuss politics. Clearly, a child in this situation would try to sound coherent, but lack the requisite knowledge to do so. I’d rather hear that same child’s self dialogue as they perceive and make sense of the world around them. When I read the freeform text output by my AI, I like to imagine that it too is learning to make sense of the world.

If a neural network is comparable to a brain, then the untrained network is the purest form of the Aristotelian concept of tabula rasa. Tabula rasa, or blank slate, is the theory that individuals are born without any mental concept and fully take form through their experiences and perceptions. Researchers designed a conversational AI which would interact with users on social media and learn from the messages received. Within a day, the AI was spewing inappropriate and bigoted content.

If an AI raised on social media turns into a hateful extremist, then I must think carefully about what I use to teach my AI. The obvious choices include classical literature, textbooks on all subjects, and a minimal curation of web content, a selection equally fit for teaching a child. But if I were to raise a child, I wouldn’t stop there; I’d also want to teach them to be excited about what excites me. I’d want them to construct nonsensical metaphors about computer science and reference just enough philosophy to support the point they’re trying to make. I’d want them to think deeply about what science that came before them and curious about how they could contribute to it. And so, I add my papers, my technical blogs, and even my journaled philosophical ramblings to the set of training materials.

I pour my coffee and open up my computer to check if my last training job has finished. Seeing that it has, I start to skim through the most recent sample output text.